When the Modoc War began, the Modoc warriors with their wives and children retreated to the nearby Lava Beds. The War was fought nearly 150 years ago, yet it stands out in American military history as the most incredible of Indian wars. Captain Jack did not muster more than 60 men throughout the War, but for almost eight months he withstood the United States Armed Forces that came to number over a 1,000 men supported by mountain howitzers and coehorn mortars. The Modoc lost only six men by direct combat while the U.S. Army suffered 45 dead including General E.R.S. Canby, the only U.S. General to lose his life in an Indian War. The Modoc War cost the United States government, at its lowest estimate, of the time half a million dollars; that would be roughly $8,500,000 in today’s currency. Considering the number of the enemy, it was probably the costliest Indian war ever fought. In comparison, the reservation requested by the Modoc on Lost River would have cost, at most, $10,000 or $180,000 in today’s currency.

When the War finally ended on June 1, 1873, Captain Jack and five of his warriors, Schonchin John, Black Jim, Boston Charley, Barncho and Slolux became the only Indians in American history to be tried by a Military Commission for War Crimes. Other captured Modoc were being transported to Fort Klamath, Oregon by wagon and were attacked by Oregon Volunteers who killed 4 unarmed Modoc men and badly wounded a Modoc woman while Modoc children were forced to bear witness. Gallows had been constructed even before the trial began, and it was evident the verdict would be death by hanging. The date set for the execution was October 3, 1873. Just before the executions were to take place, the sentences of Barncho and Slolux were changed to life imprisonment at Alcatraz Island. However, they were not informed of the change in their sentences until after they, along with the other Modoc men, women and children were forced to watch as their leaders were hanged. Captain Jack proved to be the only Indian leader executed by Military Commission for participation in one of the United States many Indian wars.

On October 12, 1873, 155 Modoc, 42 men, 59 women, and 54 children were loaded on 27 wagons and departed Fort Klamath, Oregon under the guard of Captain H.C. Hasbrouck and soldiers of Battery B, 4th Artillery. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs had decided to place them on a reservation under military guard in Cheyenne, Wyoming; however, strict orders had been given not to reveal their destination which would later be the Quapaw Agency, Indian Territory.

The first stop on their journey was one week later near Yreka, California. When they finally reached Redding, California, Barncho and Slolux were sent with their military guards to Alcatraz Island. The remaining Modoc were loaded into cars meant for transporting cattle by train, a conveyance they had never seen, for a terrifying ride to Fort D.A. Russell in Wyoming Territory. The Modoc occupied four railroad cattle cars coupled between two other passenger cars filled with soldiers. Guards with loaded rifles stood at the doors of each car day and night. All of the men and boys capable of bearing arms were heavily shackled to the floor of the train car.

Nearing Fort D.A. Russell, orders were changed due to impending military campaigns against other regional tribes, sending the Modoc prisoners to Fort McPherson, Nebraska. Arriving there October 29th, Captain Hasbrouck turned his charges over to Captain Melville C. Wilkinson, United States Army, Special Commissioner in Charge of Indian Removal. The Modoc prisoners were placed on an island in the Platte River, a few miles from the fort, where they made camp to hunt and fish for food.

The terrible 2,000-mile early winter ride in railroad cars intended for hauling cattle finally ended on November 16, 1873 when 153 Modoc men, women, and children arrived in Baxter Springs, Kansas cold and hungry.

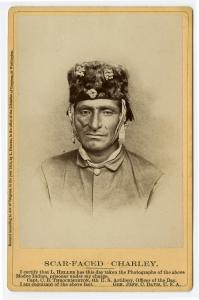

In Baxter Springs, Captain Wilkinson conferred with Hiram W. Jones, Indian Agent at the Quapaw Agency as to where to place the Modoc. It was decided to locate them on Eastern Shawnee land where they would be under the direct supervision of Agent Jones. But Jones’ Quapaw Agency was little prepared to care for 153 Indians with little but loose blankets on their backs. With Scarfaced Charley in command and only one day’s help from three non-Indians, the Modoc built their own temporary wood barracks two hundred yards from the agency headquarters. Some were housed in tents. These accommodations were to be their home until June of 1874 when 4,000 acres were purchased for them from the Eastern Shawnee.

The Quapaw Agency was located on Eastern Shawnee land in the northeast corner of Indian Territory now Ottawa County, Oklahoma. It was bounded on the north by the Kansas state line and on the east by the Missouri line. The Cherokee Nation formed its western and southern boundaries. The agency had been a sub-agency of the Neosho Agency until 1871 when they were jurisdictionally separated. The tribes constituting the Quapaw Agency were the Confederated Peoria, Eastern Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa, Quapaw, Seneca, and Wyandotte. Captain Wilkinson remained with his charges until the second week in December. When he left the agency, he reported to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, “on the cars, in the old hotel used for them at Baxter, I found them uniformly obedient, ready to work, cheerful in compliance with police regulations, and with each day providing over and over that they only required just treatment, executed with firmness and kindness to make them a singularly reliable people.” Agent Jones also found he had no difficulty enforcing the strictest discipline, although one small area of friction had developed. This was the habit of some of the Modoc in gambling, resulting in some instances in losing what few possessions they had. When Scar-faced Charley, who had replaced Captain Jack as Chief, refused to interfere, Jones appointed Bogus Charley as Chief.

The first years following removal to Indian Territory were difficult ones for the Modoc. They suffered much sickness and many hardships due to the corrupt and cruel administration of Agent Jones. During the first winter at the Quapaw Agency, there were no government funds available for food, clothing, or medical supplies. It would be almost a year after removal that funds in the amount of $15,000 were allocated for their needs.

The death rate was especially high among the children and the aged. By 1879, after six years at the Quapaw Agency, 54 deaths had reduced the Modoc population to 99. By the time of the Modoc allotment in 1891, there were only 68 left to receive allotments, and many of them had been born after removal. Had it not been for the gifts of money and clothing from charitable organizations in the east, General William Tecumseh Sherman’s wish not to leave a Modoc man, woman, or child alive so the name Modoc would cease, would have become a reality.

During the 1870’s it was common knowledge that the Office of Indian Affairs was rife with corruption and greed Indian agents assigned to look after the well-being of their Native captives were frequently involved in a system of billing the U.S. Government of resources intended for the tribes. These so-called “Indian Rings” operated on a joint conspiracy between one politician, one Indian agent and at least one local merchant. Together, the three components defrauded the government and the Indians of the resources allocated for food, medical supplies, and clothing.

In an effort to eliminate the cruelties of graft so often inflicted upon the newly dependent Indian nations, the Indian agencies were placed in the hands of religious groups such as the Society of Friends, more commonly known as Quakers. The Quakers who were in charge of the Quapaw Agency in the 1870’s were from the same Society of Friends who claim credit for successfully proposing the original Indian “Peace Policy” to President Ulysses S. Grant.

Quaker Hiram W. Jones was the Indian agent at the Quapaw Agency when the 153 Modoc prisoners of war arrived there in 1873. Jones answered to a fellow Quaker, Enoch Hoag, who was Superintendent of the Central Indian Superintendency headquarters in Lawrence, Kansas. As it happened, Agent Jones’ wife and Superintendent Hoag’s wife were first cousins. Such nepotism was not the most obvious problem with Agent Jones’ management practices.

The Modoc experience at the Quapaw Agency would prove no better than the treatment they received on the reservation in Oregon, and indeed, much worse. As historian Albert Hurtado has written, “the Modoc were victims of a Quaker Indian ring that operated at the Quapaw Agency for nearly a decade during the 1870’s”. Of the 12 agency employees, 11 were relatives of Agent Jones or Superintendent Hoag.

Soon after the Modoc were settled at the Quapaw Agency, Agent Jones restricted all trade with them to a store constructed next door to the agency building, thus eliminating all trade with merchants in nearby Seneca, Missouri. Superintendent Hoag’s first cousin, T. E. Newlin, operated the store. When Seneca residents filed numerous complaints concerning the intolerable conditions suffered by the Modoc, their claims were dismissed. It was presumed that the complaints were from disgruntled merchants who were bitter at being cut out of the lucrative Modoc trade.

Following the Nez Perce War with the United States, Chief Joseph and his people were forcibly removed from their homelands in the Northwest to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1877. Eight months later they were transported by train in sweltering heat to Baxter Springs, Kansas. The weakened and sick Nez Perce were unable to make the walk in the heat to the Quapaw Agency. The Modoc were hired as teamsters to bring them by wagons to Modoc Springs on the reservation where they set up a temporary camp. Modoc Springs would become the site of many spirited horse races enjoyed by all tribes at the agency. Agent Jones viewed the gambling that tends to accompany such events with great consternation.

The Nez Perce did not remain long with the Modoc. Less than six months later they were transferred a few miles north to the Peoria Reservation. Eventually, they were transferred to the Ponca Agency in the western portion of Indian Territory and later to Washington State and Idaho.

Hiram Jones’ swindling of the Modoc’s already meager rations of bad food and inadequate medical created such deplorable conditions that the Modoc mortality rate continued to climb. Because of persistent complaints by the Modoc and their non-Indian neighbors, Jones’ Indian Agency was investigated by the Office of Indian Affairs in 1874 and again in 1875, but few changes and no criminal charges were made as a result. It wasn’t until the third investigation in 1878 that a system of nepotism and corruption was officially reported. It was described as a family Indian ring whereby Jones and his family members would receive kickbacks from local merchants for the inflated prices and inferior quality of goods and services provided to the agency on behalf of the Modoc. Apparently, Jones’ religious convictions did not protect him from the greed enjoyed by so many of the less pious Indian agents. Still, it wasn’t until the following year that Hiram Jones and his family ring were relieved of their duties at the Quapaw Agency.

In spite of the odds against their survival, the Modoc men and women persevered and survived the cruel administration of Agent Jones by supplementing their own income in a number of ways. They rapidly took hold of their new lives, adopting the ways of the area whites and assimilated in order to survive. They worked at anything that brought them an income. The men worked on the farms of their white neighbors, hauled materials and supplies to surrounding towns. The women added to the family income by selling their bead work and intricately woven basketry. Both men and women worked in the fields. Soon they were cultivating their own land and assured their own survival by continuing to improve the condition and productivity of their farmlands and livestock herds. It was reported that they sowed and reaped with the same persistent courage with which they had fought. Furthermore, it was said that they dressed better, farmed more intelligently, kept their houses cleaner, cooked their food better and sent their children to school tidier with each succeeding year. The Modoc were regarded among the Quapaw Agency as the best of the agency’s tribes. The Modoc Indian agent reports indicate that this small band of Modoc made more progress with less land than any other tribe under the jurisdiction of the Quapaw Agency.

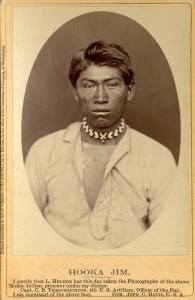

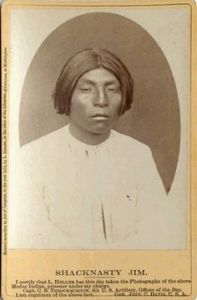

During the Fall of 1874, Alfred Meacham, one of the four peace commissioners who had met Captain Jack during the Modoc War, visited the Modoc. He was planning a lecture tour of eastern states dealing with his adventures during the war and felt it would add color and interest if some of the Modoc participants were permitted to be with him. He received permission for Scar-faced Charley, Shacknasty Jim and Steamboat Frank to accompany him on the tour.

The Modoc were very interested in obtaining an education for their children. Six weeks after removal, 25 of their children were attending the Quapaw boarding school some 12 miles north of the agency. Less than one year later it was reported the children were making excellent progress in school and were rapidly learning English. Many of the adults were also learning to read and write. In 1879, the government constructed a building on the Modoc Reservation that served as both a school and a church. Several of the children later attended Carlisle Indian School near Arkansas City, Kansas. However, after the death of Adam McCarty, a stepson of Schonchin John at Carlisle, Modoc families were reluctant to send their children away to school.